ECONOMY

Jordan’s agricultural sector produces tomatoes, citrus fruit, cucumbers, watermelons, aubergines and wheat, mostly grown in the fertile ground along the Jordan Valley. Phosphate mining and potash extraction are the traditional industries, but oil refining, chemical manufacturing, food processing, and the production of metals and minerals also contribute to this sector.

The service sector accounts for around two-thirds of total output and covers wholesale and retail trading, finance, transport and tourism.

During the latter years of King Hussein’s rule, some economic reforms based on the customary package of deregulation and privatization were instituted. These brought the country’s rampant inflation under control but failed to dent the country’s massive unemployment problem. These reforms have, by and large, continued under King Abdullah.

Many Jordanian workers have moved abroad in search of employment and their remittances are an essential means of support for many families. Jordan is a member of various pan-Arab economic bodies, notably the Council of Arab Economic Co-operation and the Arab Monetary Fund. The government liberalized the trade regime sufficiently to secure Jordan’s membership of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2000, a free trade accord with the USA and an association agreement with the EU in 2001; these measures have helped to improve productivity. Inflation in 2005 was 3.5%, while annual growth was expected to reach 7.7% in 2006.

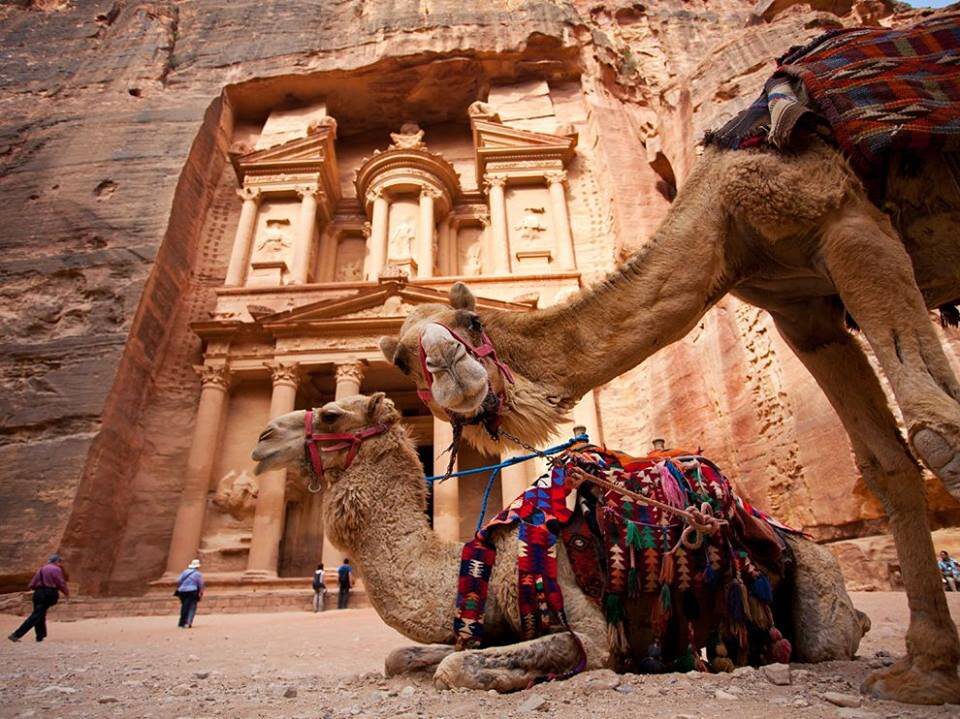

THE NABATAEANS

Jordan shares borders with Israel, the Syrian Arab Republic, Iraq and Saudi Arabia. The Dead Sea is to the northwest and the Red Sea to the southwest. A high plateau extends 324km (201 miles) from the Syrian Arab Republic to Ras en Naqab in the south with the capital of Amman at a height of 800m (2,625ft). Northwest of the capital are undulating hills, some forested, others cultivated. The Dead Sea depression, 400m (1,300ft) below sea level in the west, is the lowest point on earth. The River Jordan connects the Dead Sea with Lake Tiberias (Israel). To the west of Jordan is the Palestinian National Authority Region. The east of the country is mainly desert. Jordan has a tiny stretch of Red Sea coast, centered on Aqaba.

The country came under the rule of King Abdullah ibn Hussein, a member of the Arabian Hashemite Dynasty who had held the position of Emir since the 1920s. When King Abdullah was assassinated in 1951, the crown passed to his son Hussein ibn Talal. King Hussein assumed the throne in 1952 and ruled the country until early 1999. Jordanian history and politics since independence have been dominated by the Palestinian issue and relations with Israel. When war broke out in 1948 between the newly-declared state of Israel and the Palestinians, backed by the forces from neighboring Arab countries, the Jordanian army occupied a 6000sq km area of Palestine bounded by the west bank of the River Jordan. Until a major change in Jordanian policy in 1988, the West Bank comprised three of Jordan’s eight provinces, while over half of the Jordanian population claimed Palestinian origin. Relations between King Hussein and the Palestinians were difficult from the very start: his father was murdered by a Palestinian extremist. Jordan lost the West Bank after the Six-Day War of 1967, and gained thousands of Palestinian refugees who fled across to Jordan. Many of them joined one of the myriad of guerrilla groups organized under the umbrella title of the Palestine Liberation Organization (the modern PLO is a coalition of seven main factions, the largest of which is Al-Fatah headed by the PLO’s overall leader Yasser Arafat). Hussein ultimately came to feel that they constituted a major threat to his authority and, in September 1970, he deployed the Jordanian army to expel them. In 1973, Israel again defeated a combined Arab force, including a small Jordanian contingent, in the Yom Kippur war: Jordan lost no territory on this occasion. Throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s Jordan pulled back from regional politics to concentrate more on domestic matters. After 1967, political power in Jordan was concentrated fully in the hands of the King and his Council of Ministers. Political parties and almost all political activity were banned.

This prohibition has been substantially relaxed since the mid-1980s to the point where political parties can now campaign openly for election. Nevertheless, the government continues to restrict their activities and is especially wary of any manifestations of Islamic fundamentalism which, as elsewhere in the Arab world, has been growing in Jordan. Most political parties boycotted the most recent parliamentary poll in November 1997 – the only officially represented political party is the small Ba’ath party – and the National Assembly remains, as previously, dominated by supporters of the King. The Palestinian problem re-emerged as a major factor in Jordanian politics with the onset of the first Intifada (the uprising by Palestinians living in Israeli-occupied areas) in 1987. This led, in July the following year, to a surprise decision by Hussein to cede the residual Jordanian interest in the internal affairs of the occupied West Bank (notably the financing of public services such as education). Then in 1990, another of Jordan’s other neighbors, Iraq, became the cause of major problems for the Jordanians when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. The ensuing Gulf War of 1991 proved a political and economic disaster for Jordan. Traditionally friendly to both the US and Iraq and, in different ways, economically reliant on both, Jordan was forced into an unwelcome choice. Inevitably, Jordan lost out with both sides through its failure to give wholehearted support for the US-led coalition which defeated the Iraqis, and by accepting large numbers of Iraqi refugees. During the rest of the 1990s, Jordan suffered badly from the UN sanctions imposed upon Baghdad and it has benefited significantly from the gradual disintegration of the sanctions regime.

The Iraqi situation also had the effect of pushing King Hussein into a peace agreement with the Israelis, allowing for security and economic cooperation, which was concluded in 1991. Since 2000, and the second Palestinian Intifada, this agreement has come under serious strain.

By this time, moreover, there had been an important change in Jordan. King Hussein’s health had been in decline throughout the 1990s and he died of cancer in February 1999. The King’s brother, Crown Prince Hassan, had long been the heir apparent. But the King had stipulated before his death that one of his sons, Prince Abdullah, had been chosen to take over upon his death (Hassan remains an important figure in the regime). During his first year in office, Abdullah adopted a more populist style than his father but there has been little change in the substance of policy. A new Prime Minister, Ali Abu al-Ragheb, took office during 2000 at the head of a government composed of independents and members of the main Islamic bloc.

During 2002, Abdullah was confronted by the same dilemma as his father as, once again, the Americans have Iraq in their sights. There is strong anti-American feeling in the country due to the Bush administration’s support for Israel and its proposed assault on fellow Arabs. The government is also deeply concerned about the economic consequences of a second Gulf War. The regional situation lay behind Jordan’s decision to cancel the planned Non-Aligned Summit, scheduled in Amman in April 2002. Jordan’s planned takeover of the presidency of the movement from South

Africa is now in jeopardy.

Elsewhere, Jordan has cut diplomatic relations with Qatar over a broadcast by the al-Jazeera television station (famous as the main outlet for the al-Qaeda terrorist set-up) which criticized alleged corruption within the Jordanian government.

Government

The Mamluks repelled the Mongol invasion of the 14th century but were eventually overthrown by the Ottoman Turks in 1517. Jordan was governed along with modern-day Palestine and Syria as a single administrative entity (called a vilayet). Turkish rule lasted, in an increasingly anaemic form, until the beginning of the 20th century. After World War I, when the major Western powers began to dismember the old Ottoman Empire and distribute its territories among themselves, the area east of the Jordan River, known as Transjordania, fell to the British. Like neighboring Palestine, Transjordania came under a League of Nations mandate under which the British maintained control. The mandate ceased in 1946, at which point Transjordania attained full independence under the present constitution.