Exploring the Historical Significance of Qasr Al-Hallabat : Unveiling Layers of Transformation

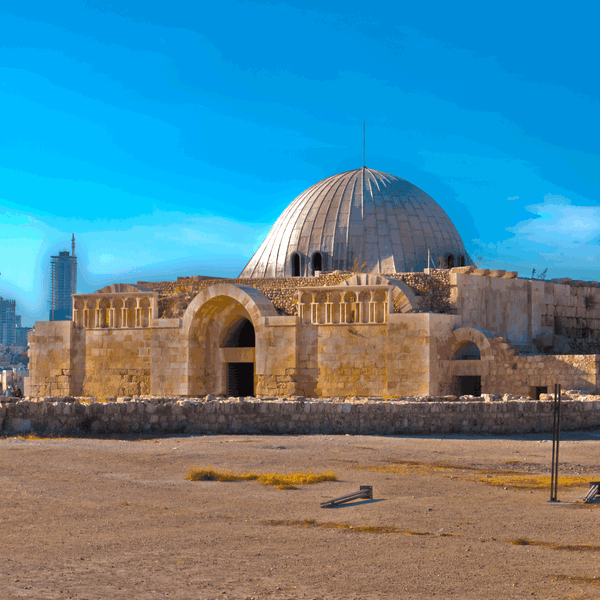

Located 60 kilometers northeast of Amman, the Hallabat complex stands as a testament to the strategic importance it held during the 2nd and 3rd centuries, a pivotal era marked by the decline of the Roman Empire and confrontations with the Sassanid Empire. This historical site, comprising a mosque, baths, and various structures, played a crucial role in the complex geopolitical landscape of its time.

In the midst of the “Crisis of the 3rd Century,” Hallabat witnessed the capture of Emperor Valens at Edessa in 260 AD, marking a dramatic setback. Situated on Via Nova Triana, linking Damascus to Ayla (modern-day Aqaba), it served as a military stronghold, fortifying the eastern frontier against external threats.

Over time, the site underwent multiple transformations, transitioning from a strictly military post to a more civilian shape. Notably, unexpected discoveries emerged, such as the coexistence of a monastery and a pre-Umayyad palace within the same precinct. Rigorous scrutiny and double-checking of data preceded their presentation to the scientific community, ensuring accuracy.

Spanish professor Ignacio Arce, affiliated with the German-Jordanian University, highlighted the cautious evolution of hypotheses. Initially proposing the existence of a Ghassanid palatium during the 6th century AD, subsequent excavations revealed new evidence leading to the interpretation of Hallabat as a reoccupied, rebuilt, and transformed monastery and palatine complex after the dismissal of the Ghassanids-Emperor Justinian agreement in 529 AD.

Emperor Justinian’s military reforms in the 6th century AD had a direct impact on the Limes Orientalis, the Byzantine Empire’s eastern frontier. The Ghassanids, serving as phylarchs, played a crucial role in unifying local tribesmen as the first line of defense. The fortifications at Hallabat and similar sites were strategically positioned to control water sources, vital for the Ghassanid outposts.

Monasteries emerged as key defensive structures, with fortified towers serving as watch posts alerting nearby military stations. This symbiosis between monasteries and camps gave rise to a landscape of permanent buildings, exemplified by the structures at Hallabat. The Ghassanids, active in their defense, contributed around 5000 cavalrymen and established their main base in Gaulanitis (modern Golan).

In conclusion, Hallabat’s historical narrative unfolds as a dynamic interplay of military strategy, geopolitical shifts, and unexpected coexistence, offering a window into the complex tapestry of the region’s past.